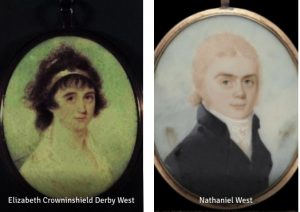

Miniature Portraits of Captain Nathaniel West and Elizabeth Derby West

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass.

Captain Nathaniel West (1758-1851), who built the Salem Inn’s West House in 1834, eloped with the daughter of Elias Hasket Derby, Elizabeth “Betsey” Derby, in 1783. Elias Derby owned or held shares in many privateering ships during the American Revolution, which made him one of America’s first millionaires (which in today’s money is about 21 billion dollars). Initially he did not approve of the marriage, as West was a commoner and Derby’s family was rich. Elizabeth had married below her station in life. She soon found herself ostracized by high society, and was no longer included in charitable organizations and social gatherings. She was now only Mrs. West. However, her father took to Nathaniel and eventually he employed him as a captain and privateer on of one of his ships. He became one of the most successful sea captains from Salem during the China, West Indies, and Indian trades. He too became rich.

The marriage was not a happy one. In 1803, the Wests separated. West moved out of the house Elizabeth had been bequeathed from her father, a farm called Oak Hill, in nearby town of Danvers, MA. (The spectacular, lavishly appointed interiors of three of the rooms can be visited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Oak Hill Parlor

Boston Museum of Fine Arts

But they did not divorce, not right away. Divorce was very unusual at the time but not unheard of, or illegal. However, Elizabeth waited to make her move.

Before 1806, when a husband and wife married, the husband was granted all the wife’s property in exchange for taking care of his wife and family. If they divorced, the husband retained two-thirds of both his properties as well as the those that had originally been his wife’s. The property left to the woman was called a widow’s third. However, in 1806, the laws changed and the wife was entitled to any property and monies her husband held in her name. In Elizabeth’s case, this was significant, as her father had left her 1/7 of his estate upon his death and other lands. There was a catch, however. The wife would have to prove the husband guilty of adultery.

In order to do this, Elizabeth trotted out a number of prostitutes from houses of ill repute in Marblehead, Salem, Boston. and Gloucester. Nathaniel’s defense was that Elizabeth had paid these women to testify. She claimed she had written proof that he has been financially sustaining a child he had sired out of wedlock, as well as a letter from a woman who claimed that he had fathered two of her children. It was an ugly scene, and tongues were wagging.

Elizabeth won the war, and was granted Oak Hill and $3,000 a year in alimony. While today we may applaud her shrewdness, independence, and courage, in 1806, she sadly gained public scorn: people would get up and leave church if she came to take communion, and she was no longer welcome in private homes and gatherings. She stayed in Oak Hill until her death in 1814, and bequeathed it to her three daughters. She forbade them to give any portion of the house back to Nathaniel.

In 1819, their daughter Sarah, who was dying of tuberculosis, willed her third of the house back to her father with whom she was close. He then proceeded to divvy up the house and move his portion by oxen to wealthy Chestnut Street in Salem, and build a back end on the four rooms, creating a lovely Federalist mansion. The house is now called the Phillips’ House, after the family who lived there last, and is open to the public.

Phillips House

Also close to her father, Nathaniel’s middle daughter Elizabeth deeded her interest in Oak Hill to her father in 1826. In 1840, Martha deeded the last third of the estate to Nathaniel as well.